BBC News NI agriculture and environment correspondent

BBC

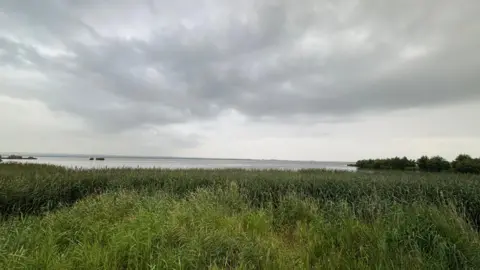

BBCLough Neagh fishermen have said that pollution “cannot be allowed” to bring an end to eel fishing on the lough.

Brown eel fishing will not resume in the area this year due to environmental changes.

Seventh generation eel-fisherman Gary McErlain called the cancellation “unprecedented”.

It comes after the reduced fat content of the eels meant the early catches were rejected by the continental market that usually prizes them.

In the meantime, eel fishermen like Mr McErlain are having to turn their attentions elsewhere.

“It’s fair to say there’s other fish to fish for in Lough Neagh, which is a blessing and a lifeline for us,” he told BBC News NI.

“But to think that with all we’ve gone through for generations and the fight to maintain the right to fish, that we’ve got to a stage where pollution is the thing that potentially could bring this to a close? That cannot be allowed to happen.”

The Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute (AFBI) monitors the eels on an annual basis.

In a statement, the research body said numbers of glass eels entering “Lough Neagh so far in 2025 have been higher than recent years up to this date” and that numbers are “primarily dependent” on these young fish surviving the journey across the sea.

The eel feeds on larvae of the Lough Neagh fly, in the bed and water of the Lough.

AFBI said it had taken a “very limited sample of brown eels” on the day the fishery closed and recorded the larvae in 35% of the stomach contents analysed which is higher than recent, larger samples.

Lough Neagh Consultation

A consultation on proposals to improve water quality was branded out of touch by farmers, who said the plan did not recognise the day-to-day reality of agriculture.

The backlash led to the consultation period being extended, and then the announcement that a review group would be established when it closed.

Proposals from that group will then go to further consultation, with a final document to be brought to the Executive for approval as soon as possible.

That move led farming leaders to encourage people to respond to the consultation.

But they are still concerned about the “very severe potential impact” of the plans, according to Jason Rankin from the industry body AgriSearch.

“We’re estimating that Daera’s (Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs) target for 2029 of an eight kilogramme phosphorus surplus per hectare could have an impact across the Northern economy of approaching £1.6 billion”, he said.

The group has called for “a win-win mentality”, with “solutions and innovation to address the water quality issues we have in Northern Ireland while protecting the agricultural sector”.

Some farmers already take a different approach.

County Down dairy farmer Tim Morrow has made changes over the years to reduce his fertiliser and feed inputs.

He has planted multi-species swards across his fields and plans to entirely move away from fertiliser use over the next decade.

But he can understand the fears of farmers who were encouraged to intensify.

“Farmers were asked to produce more food and that’s exactly what they’ve done – they’ve put up bigger sheds, they carry more cows. And all of a sudden, there’s an about-turn,” he said.

“If you’ve something that’s working, it’s very hard to change.

“l would love to see incentive-based change, encouragement for change, rather than penalties and that way for change.”

PA Media

PA MediaSpeaking to the BBC’s Good Morning Ulster programme on Friday, DUP MP Carla Lockhart acknowledged that “NAP has been around for 20 odd years and farmers have been working extremely hard at the advice of the department in trying to improve their processes”.

However she said there are “about 40 proposals within this new NAP document and they just go too far too soon”.

“Farmers are required to implement these proposals within two years – that is unachievable financially.”

She said the new proposals “will put many of our famers at risk” and “will lead to destocking, it will lead to farmers having to purchase additional land, just to meet the targets”.

“Yet the department is coming up with no assistance for farmers to actually meet it,” she added.

Agriculture Minister Andrew Muir acknowledged that one of the main pieces of feedback from the consultation was “that we need to take prompt and swift action to improve the water quality”.

The Ulster Farmers’ Union said they’re “very aware that we’re not doing all the polluting. There’s a water company or two that maybe need a bit of work and a lot of farmers feel they’re being picked on here”.

It also warned that the draft proposals could see farmers having to reduce their livestock numbers.

“If there was a programme saying, over the next five to 10 years, you’re required to be doing this – mixed swards, more hedges – there are things that can happen if people are given enough notice,” said Mr Morrow.

The Nutrient Action Programme (NAP) is a legal requirement.

It is reviewed every four years, with this latest version already several years overdue.

When it was first introduced in 2007, it led to improvements in water quality.

But Daera says those have largely been offset by the intensification of agriculture since 2012.

Agricultural pollution is the biggest contributor to the blue-green algal crisis in Lough Neagh.

Other sources of pollution, like wastewater treatment, industrial effluent and septic tank seepage also play a part.