It was a viral video of a group of cheetahs taking down a wildebeest that triggered Big Cat People, Jonathan and Angela Scott, to put together their latest e-book, Safari Etiquette: An essential guide. “There were five male cheetahs, unusual to have such a big coalition, and in October 2022, two of these cheetahs ended up nailing a wildebeest,” Jonathan says. Within seconds of their kill, they were surrounded by vehicles filled with overexcited people, egging the guides and driver to go even closer.

“It is the paparazzi effect, isn’t it? People behave really badly when there is something they want to see,” says the Kenya-based wildlife photographer and conservationist, the popular co-host of the BBC’s long-running nature documentary series, Big Cat Diary. On a safari, charismatic large animals often end up becoming celebrities of sorts, and, as with stars, “we are innately curious…want to get a closer look,” says Jonathan, whose new e-book explains precisely why one should not behave like this on a safari. “No image is worth causing distress to a vulnerable animal, prompting it to move and possibly putting it in danger,” it states.

Safari Etiquette: An essential guide, a joint initiative of their NGO, Sacred Nature Initiative, and the Narok County Government’s One Mara Brand, has been brewing since 1974, when Jonathan went out on a game drive as a visitor. “We were travelling overland from London to Johannesburg…four months, 6,000 miles,” he says. When the truck reached Serengeti, the ranger who had been guiding the group along spotted a leopard at the base of a tree and pointed it out to them. “We asked the ranger if it was possible to go a little bit closer,” remembers Jonathan. The man refused, claiming that they were not allowed to and that if the park’s warden spotted him, there would be significant consequences. “So, I saw, from the beginning, what a good guide looked like, which, to me, was to give the animal the space to breathe,” he says.

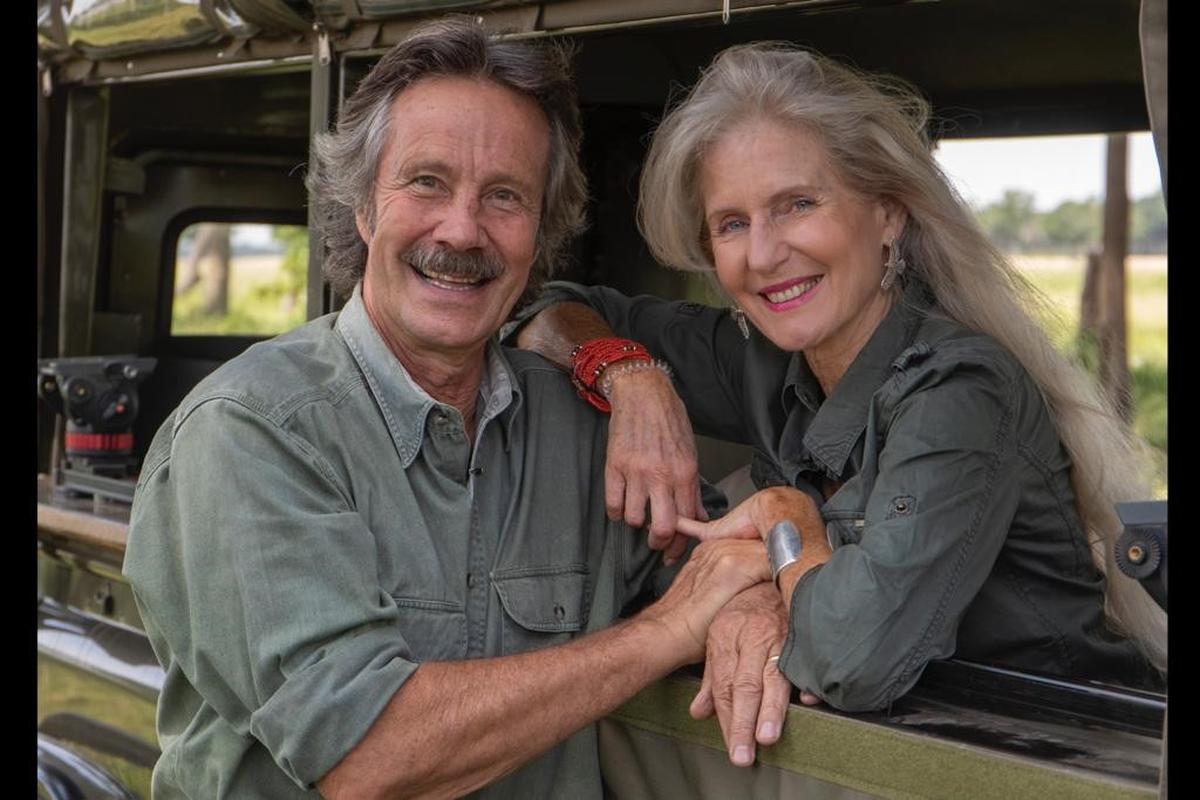

Big Cat People, Jonathan and Angela Scott

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Jonathan and Angela Scott

Much has changed since Jonathan first went on that game drive and settled permanently in Maasai Mara in 1977. “When I first came to live in the Mara, there were maybe five camps and lodges in an area of 1500 square kilometres,” he says. Now, there are over 200, “more than 5,000 beds,” he says. “I have watched this ridiculous explosion of camps and lodges driven not by sound management practices but by economic greed.”

In the Mara, this “epidemic of aggressive tourism, which is global”, had led to a chaotic situation, in his opinion. With the mushrooming of the camps and lodges, also comes the exponential increase in the number of vehicles being allowed to traverse through the Mara, “roaming in a way that has nothing to do with good guiding or following proper protocol,” he says, adding that the safari etiquette book, the rules of which are relevant to any part of the world, is not rocket science, but pure common sense.

A male lion at Botswana’s Chobe National Park

| Photo Credit:

The New York Times

For instance, according to the e-book, camps and lodges should provide guests with a comprehensive briefing before they set out on their first game drive. “It is much easier to remind visitors to be quiet and respectful when they see their first lion and are overwhelmed with excitement and emotion, if they have been briefed properly before departing from camp,” it states. Some other pointers include listening to your guide and driver, never getting out at river crossing, being courteous and considerate when approaching a sighting, never encircling wildlife and blocking their entry and exit pathway and backing off while watching a mother with her young, if she appears nervous. After all, “this is not a circus, theme park or zoo, but real, wild Africa where animals are living and dying,” he says.

Wildebeests run across a sandy riverbed of the Sand River as they enter Kenya’s Maasai Mara National Reserve from Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park during the start of the annual migration

| Photo Credit:

AFP

In the age of social media and selfies, unfortunately, the safari business is driven by getting a shot at all costs, rues Jonathan. “Nothing else matters…ethics go out of the window…even decent behaviour,” he says. And the cost of this is borne by wildlife. As much recent research has demonstrated, rampant tourism can have a significant impact on wild animals, altering their behaviours and habits, even endangering their lives.

Safari Etiquette: An essential guide explains how one must behave on a safari

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Jonathan and Angela Scott

Jonathan highlights one such telling piece of research: a researcher who was doing a cheetah monitoring project for the Kenya Wildlife Trust discovered that in high tourist areas, cheetahs raised fewer cubs to independence when compared to those with lower tourist footfall. According to him, often, when a cheetah mother got up to hunt, she would be relentlessly followed, impacting her ability to find sufficient food for her cubs,” he says. Additionally, if the cubs are young and the vehicle gets too close to them, she would have to move them and risk running into predators like hyenas and lions in the process. “This is a living, breathing, very smart creature, and the least we can do is be respectful. No photograph should be worth a cost to the subject.”

Published – July 30, 2025 05:46 pm IST