A chintz panel at the studio

| Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

In a quiet studio in Adyar, a small but dedicated team is piecing together what history has almost let slip away — India’s once-thriving Coromandel textile traditions.

At Aksh Weaves and Crafts, textile reconstruction is not a nostalgic exercise, but a painstaking act of archival research, material experimentation, and artistic revival. The work is slow, often invisible, and entirely self-funded — but to the team behind Aksh, it is essential.

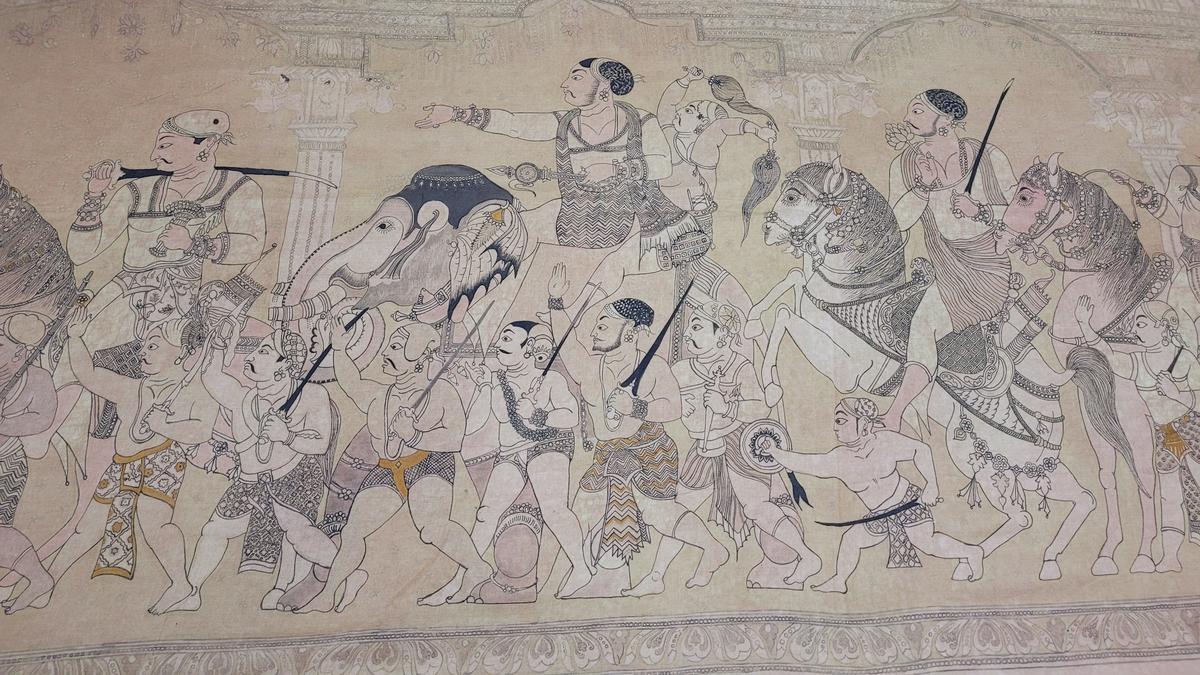

A Nayaka Kalamkari panel

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

For founder-researcher Sriya Mishra, textile revival is not about boutique fashion or nostalgia marketing. It is a long-haul archival practice, one that lies at the intersection of historical research, fine art, and intangible cultural heritage. “We work in the cross-section of archives and art,” Sriya says. “Each piece can take close to four years of research before we even begin the process of recreating it.”

Their efforts have brought back to life textiles like Kodalikaruppur, a richly layered fabric once worn by royalty in the Thanjavur region and previously deemed too complex to reproduce. Other recovered designs include Nayaka Kalamkari, associated with the chieftains of the Vijayanagar empire, and chintz, a glazed calico cotton cloth that once dominated India’s textile exports to Europe and America. The recreation itself involves several complex processes — scouring and desizing to soften the fabric and remove impurities, dyeing the fabric with natural madder and indigo dyes, before finally hand painting intricate details with kalams. “Each piece takes between three to six months to complete,” explains Sriya.

These are not just textile designs but vehicles of material history, reflecting centuries of diplomacy, migration, and artistic patronage — making Aksh even more extraordinary when taking their global range into account. In addition to working with Indian-origin textiles, they have also recreated Sarasa — a Japanese adaptation of Indian chintz — making them the only studio in Asia to do so. “Many of these techniques, especially hand-drawn and resist-dyed forms, vanished over a century ago,” says Sriya. “Even textile experts today have never seen these in their original form.”

The studio has worked on Sarasa — a Japanese adaptation of Indian chintz

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Everything at Aksh is handwoven, naturally dyed, and rooted in rigorous, first-hand archival work. They rely on rare fragments, museum records, and indigenous dye knowledge — some nearly lost to time. Every motif, brushstroke, and even the placement of figures in a palace court scene is historically verified, down to the protocol of where a king’s adviser might have stood.

The work is entirely self-funded, driven by a tight-knit team of graduates from fine arts and communication colleges who are as committed to historical accuracy as they are to artistic revival.

Sriya says she wants these designs to exist again, not as relics behind glass, but as living art.

Published – August 07, 2025 02:52 pm IST