BBC NI agriculture and environment correspondent

BBC

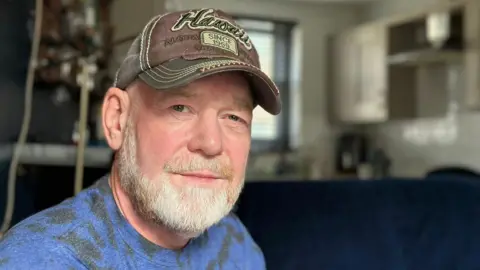

BBCThe ground that Emmanuel Burns’ County Antrim apartment block is built on has significantly reduced his energy bills since he moved in 18 months ago.

The Rural Housing Association complex in Randalstown in County Antrim uses the heat of the earth itself to warm rooms and heat water through a geothermal system – pipes dug down into the ground to reach the renewable heat stored there.

Northern Ireland has been identified as one of eight “Goldilocks” regions in the UK with just the right conditions for accessing geothermal energy, thanks to the rocks beneath the surface.

The only equipment Mr Burns needs is a thermostat on the wall.

“It’s pretty easy to use, you can adjust the heating to whatever you want – from 14 degrees to 26,” he said.

“Before I moved in here, I was paying £20, £30, £40 a week for heating, whereas now it’s £15 a week.

“That’s your heating day and night, your hot water, your air conditioning and you’re making a saving every week, which adds up throughout the year.”

All nine apartments in the block are connected to six boreholes hidden beneath the car park, via two units located in a separate plant room.

The boreholes tap into water that was stored in layers of Sherwood sandstone as the rock formed over millennia.

That water heated up, depending on how deeply it was stored.

The machines in the apartment block plant room extract the water, compress it to extract the heat, and then pipes feed that heat around the complex.

Sherwood sandstone is found across Northern Ireland at different depths.

The British Geological Survey says that makes it a “Goldilocks” region – just right – for a number of green energy opportunities, including geothermal.

Geologists say there is potential for secure, affordable, sustainable energy and skilled job creation as a result.

“The principle is that the deeper you go into the earth, the warmer it is,” said Dr Marie Cowan, director of the Geological Survey of Northern Ireland.

The porous nature of Sherwood sandstone makes extracting that heat possible.

“You can either use a closed loop system and drill into the earth and put it through a heat exchanger to decarbonise a home, a hospital, a school, a public building,” she said.

“Or you can go deeper still, where there’s a greater opportunity for warmer temperatures and tap that into a heat network for a town or a bigger estate that needs a greater heat.”

The technology has been used for decades in parts of Scandinavia, but we are only “catching up a wee bit now”, according to Ryan Daly from Daly Renewables, who installed the system at Mr Burns’ apartment block.

“The benefits of this is that the system itself is about 300 to 400% more efficient than a typical gas or oil boiler,” he said.

“Typically it will have less maintenance than a boiler system.

“The technology has proven to be reliable, it’s efficient, it helps save on carbon as well.”

Pilot geothermal projects were launched in Antrim and at the Stormont Estate in east Belfast in 2023 to test the potential.

Can it be scaled up?

The question is, can the results of these studies be scaled up across Northern Ireland?

Dr Cowan believes they can.

“Whether it’s further drilling, deeper drilling or more studies, the idea is to de-risk that [geothermal] opportunity for the whole of Northern Ireland.

“So whether you’re in the private sector, public sector, a local council and education authority, a health trust, you can use that information and help decarbonise your estate.”

That also creates potential for skilled jobs in the mechanical, electrical and plumbing industries.

Northern Ireland has targets for reducing its greenhouse gas emissions and increasing its renewable energy use, which industry experts have warned are likely to be missed.

Transforming how we heat our homes has a role to play in meeting those targets.

But Northern Ireland is the only part of the UK and Ireland not to have a renewable energy support scheme in place for private residential properties.

The Department for the Economy has consulted on proposals to support the decarbonisation of residential heating.

It has been a complete turnaround for Dr Cowan over the course of her career.

“I was coming to look at these rocks for oil and gas exploration,” she said.

“How the world has changed since then.

“Twenty-five years later, we’re looking at the same rocks with a totally different lens – an opportunity to decarbonise the planet and make up for the legacy of that industry.”